A good portion of the following has been drawn from an earlier post at English Language and Usage at Stack Exchange . You can see it in its entirety here

Ever wonder about those asterisks and other bleeping marks used to shield us from those “unpleasant” and “socially unacceptable” words. What are they called? Where the f**k did they come from?

As a social service for the more literate reader s of this blog (You know who you few are), I have done some research on your behalf. You know research. It’s stealing other people’s work and riding their backs to fame and fortune. Meanwhile, the rest of you illiterate, sex-starved readers can simply skip this entry and go on to more salacious material which requires less grey matter.

My humblest and most sincere apologies to the two sites from which I have literally lifted most of the following material; but my loyal man-servant, secretary, and researcher, igor, failed to record the source of the following. But f***k it!. No one really gives a s#*t anyhow. So here goes nothing.

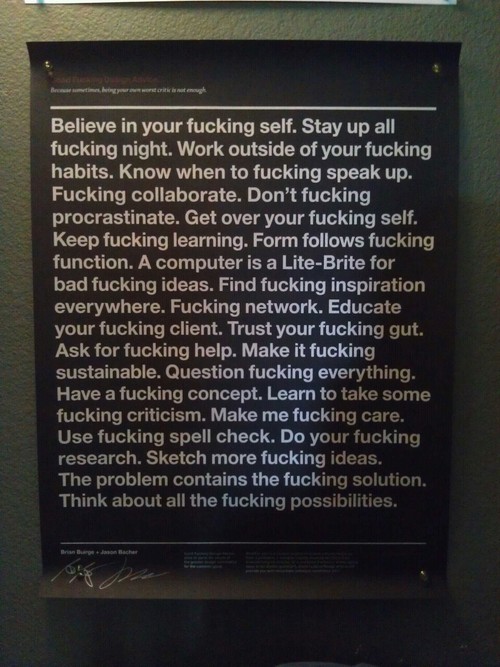

The most term invented in 1980 to describe textual symbols meant to represent profanities is “grawlix/grawlixes”. Other suggestions for the same thing are “obscenicons” or “maledicta”. These refer to e.g. old comic strips in which the dialog bubbles of characters sometime contain expressions like “@#*!%!”, meant to represent a profanity.

The use of typography to censor words was originally used to avoid breaking obscenity laws, when it was blasphemous to make fun of religion. Religious words were censored more than “normal” swear words, and were only censored when used as part of oaths; normal use was unbleeped. Dashes were used to obfuscate throughout the 18th century and asterisks were common from the 19th century on.

1710

Eliminative dashes, as in D–n for Damn can be found as early as 1710 in The Tatler (found via The Anatomy of Swearing (2001) by Ashley Montagu):

D—n you all, for a set of sons of whores; you will stop here to be paid by the hour! … Why, and be d——d to you, do you not drive over that fellow?

1687

Earlier than then Rigby sodomy trial of 1698 is this citation in the OED for shit:

a1687 Duke of Buckingham Instalment in Wks. (1705) II. 88 You’re such a scurvy..Knight, That when you speak a Man wou’d swear you S——te.

1688

Mark Liberman of Language Log searched LION (LIterature ONline) and found Richard Ames’s “A Satyr Again Man”, from Sylvia’s Revenge (1688):

314 Bully how great i’th’ Mouth the Accent sounds;

315 Bully who nothing breaths but Bl—d and W–nds?

1680

The same Language Log post has John Oldham’s poem “Upon the Author of a Play call’d Sodom” from Works (1680):

26 Whence nauseous Rhymes, by filthy Births proceed,

27 As Maggots, in some T—rd, ingendring breed.

1684

Jack Horntip has a fascinating collection of books from the 17th century to today. Several contain typo-bleeping, but it may be that some of them are later (sometimes 19th century) reprints with censoring added at the later time, and the originals may have been uncensored.

The following are all from the Jack Horntip Collection and most only show the raw OCR (plain scanned text). It’s possible they’re from later printings, but from the first pages I get the impression they’re the original typography. However, they could be later, edited, “facsimile” re-printings, as I’m unsure if the years would be written in Roman or Arabic numerals at this time. (These should all be available online in the Early English Books Online database for further verification.)

The earliest that has a full PDF is in Sodom or the Quintessence of Debauchery (1684) by the Earl of Rochester, which is chock full of all sorts of uncensored sexual language but bleeps out “heaven[s]”, “almighty”, “God[s]” (although there’s a single “p—s”), for example:

Al . . . ty Cunts, whom Bolloxinion here

Say what you want, but be careful of the Church!

1675

Mock Songs and Jovial Poems (1675):

You’d find the Perfume,

Almost as strong as it was:

Nay, she had such an Art,

In Letting a F—,

I mean for the Noise and Smell;

1672

Covent Garden Drolery 2nd Ed. (date also shown on the scanned first page):

Now he that sate here had much the better pjace,

He broke not his Neck, though he wetted his Ar—

For by th’ill successive disposure of th’other

Folks saw, and they tumbled too, one o’re another,

1658

Wit Restor’d by John Mennes issued in 1658:

In rythem daigne goddess to accept my verses,

I wis with worse wise men have wip’t their A—

O thou which able art to take to taske all

(Pox! what will rythme to that?) oh, I’me a raskall,

1658

The earliest I found is John Philips’ Sportive Wit (1656) and contains many bleepos. Here’s one poem.

On Tobacco.

When I do smoak my nose with a pipe of Tobacco after a feast,

Then down let I my hose, and with paper do wipe mine — like a beast.

It so doth please my minde,

It doth so ¿ase behinde,

For to wipe,

For to wipe my ¿ewel.

Tobacco’s my delight,

So ‘t is mine to sh —

Oh fine smack,

Oh brave ¿ack my jewel.

Th-th-th-at’s all, folks.

From the desk of Dr. Bawdy and the website

www.bawdylanguage.com