We’re most nuts about our balls (10thC), the term by which we know them best. Balls have demonstrated exceptional versatility and service to the language. If you’re looking for courage, look no further. It takes balls to acquit yourself like a man, often balls the size of watermelons. Even Hemingway’s heroes required real cojones (Spanish for balls) in order to show grace under pressure. Ever so necessary, they’re unfortunately not always sufficient. As Fast Eddie Felson (Paul Newman) reminded Vince (Tom Cruise) in The Color of Money (1986): “You’ve got to have two things to win. You’ve got to have brains and you’ve got to have balls. You’ve got too much of one and not enough of the other.”

Newspapers seldom have balls in such matters. As part of a policy adopted in 1993–94, The San Francisco Chronicle sup- presses even the hints it formerly gave readers to “offensive” words (e.g. sh-t or a—hole), choosing now to either omit them altogether or use in their stead “cute” equivalents, such as “Spaldings” (a trade name for sports equipment) for balls.

The oldest English word for the testicles that we have on record is the beallucas (before 10thC). We later had the ballokes (c. 1382) or ballocks and the verb to ballock (19th–20thC), from which we got our “Ballocky Bill the Sailor”—a ballsy old salt if there ever was one. Time and his yearning for acceptability would mellow him into the children’s favorite, Barnacle Bill, with hardly a hint of his salacious character.

Part 1 Part 2

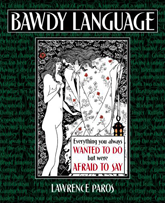

Read more – “Bawdy Language,” the Book

Leave a Reply