Archive for January, 2014

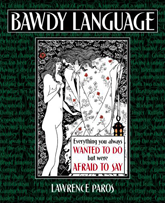

Looks can be deceiving. Though the cock appears jaunty and confident, he’s anything but cocksure. He may think of himself as a strictly all-male bird, but a close look at his history shows quite the contrary. Not only does this most masculine of birds have a feminine side to him, but, according to the lexicographer of black English J. Dillard, he once denoted exclusively the female organ in the black community of the Southern United States and the Caribbean.

This usage originated in nineteenth-century England where women oft times used cock as a verb in a passive sense, as to want cocking or to get cocked. From there, it was a natural transition to refer to the female pudendum as a cock. The male cock’s stature has further been diminished by invidious comparisons with other birds, treating its appearance and character with even less respect.

“Esther, have you ever seen a man?”…

“No,” I said. “Only statues.”…

I stared at Buddy while he unzipped his chino pants…

He just stood there in front of me and I kept staring at him.

The only thing I could think of was

turkey neck and turkey gizzards,

and I felt very depressed.

—Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, 1963

Man has always been of two minds in dealing with his prick. It’s been both an object of great pride and of great shame. In ancient times it was treated with reverence, worshipped as the source of fecundity and perceived to be the power behind motherhood, fertility, food and the seasonal cycles. In Egypt and Greece symbolic representations of it, huge phalluses (late 18th–20thC From the Greek for prick), were carried about in solemn religious processions. In Rome, images of pricks could be found everywhere. There were pricks at the doors of shops, pricks at the city gates, and pricks attached to the chariots of famous generals. Even drinking glasses and goblets were cast in their shape.

There was a young lady named Glass

Who had the most beautiful ass — Not round and pink

As you might think

It was gray and had ears and ate grass.

—Anon., 19thC